Seven years ago, BuzzFeed’s Mark Slutsky wrote about “Sad YouTube,” the comment sections underneath old pop songs that had become “a repository of memories, stories, and dreams, an accidental oral history of American life over the last 50 years.” I found out about this article because I’d noticed the same thing, tweeted about it, and the Boston Globe’s Kevin Slane said: Oh yeah, Mark Slutsky wrote about that already.

This was a major setback for my plan to post about Sad YouTube as if I’d discovered it, but only a minor setback for my plan to write something about this. Like you, I sometimes fall down a YouTube worm hole, following the prompts to an old pop song I liked already or one I’d never heard before. In the last few months, turning 40 and feeling not too great about it, I found myself spending more time poking through these YouTube threads and feeling surprisingly enriched.

That, as Slutsky points out, is not the normal feeling you get from YouTube. But this is why Sad YouTube turned into one of my favorite stops in (awful, sorry) the Metaverse.

Here’s what we’re talking about. Think of a popular song with some minor chords and sad or sadness-adjacent lyrics. I just did so and came up with “Throwing It All Away,” one of the 23 hit singles from Genesis’s “Invisible Touch” album. Here are some of the lyrics.

Someday you'll be sorry

Someday when you're free

memories will remind you

that our love was meant to be

But late at night when you call my name

the only sound you'll hear

is the sound of your voice calling

calling out to me

Just throwing it all away

The enlightened Substack reader of December 2021 might read that and think: “Jesus, Phil Collins, get over yourself.” (As we learned in a subsequent Genesis album, Jesus does know Phil Collins.) In my life, I’ve discussed this song with maybe four people: My dad, my friend Chris, my friend Rich, and someone whose name will come to me at 11 p.m. or so when I’m changing out the laundry.

But on YouTube, in a few seconds, I encountered people with deep connections to this music. Some people hear it and think of their inevitable deaths.

Some people hear it and go to a very bleak place, though not too different from the one Collins was in.

Some people hear it and have happy memories that make you wonder: Do they know what this song is about?

And some people hear it and celebrate a well-fought victory over the tastemakers.

Who are these people? I’m willing to bet that “Jessica Palmer” walks around in the real world and if I checked her ID it would say “Jessica Palmer.” This probably isn’t the case with Don K. Kong. I will never meet anyone on this thread, and I don’t need to.

Like me, they watched this video and typed some words into a little glowing box, for free, almost certainly while procrastinating.* They typed up a little personal story, with the maximum reward for their soul-bearing being a few dozen other people clicking a thumb’s up button, and the maximum risk being those people clicking a thumb’s down button.

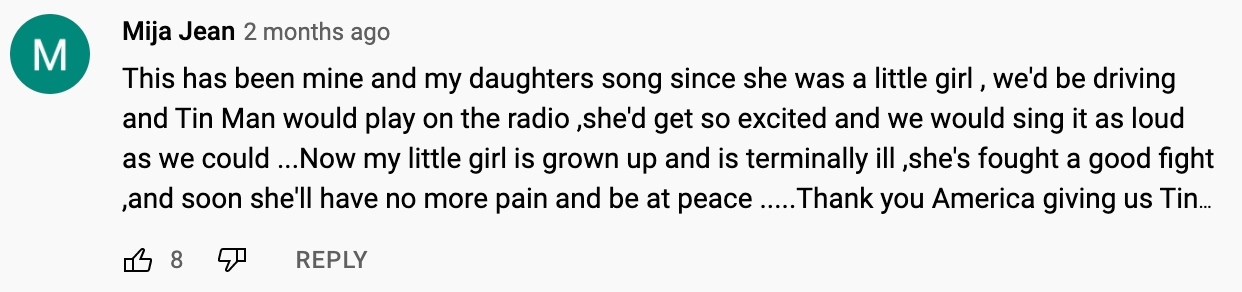

Nobody submitted anything to a literary journal. Most people didn’t use their real names. We know nothing about their lives, but for 10 seconds, we get to know them as well as anyone we’d get seated next to at a wine dinner. Maybe better — what’s your typical reaction if you’re at a friend of a friend’s wedding and the person next to you starts talking like this about the America song “Tin Man”?

Maybe you ask about her daughter. Maybe you say “that’s so sad” and excuse yourself to dance to “Blurred Lines,” a song that will be played at the wedding but has no associations with terminal illness. More likely, this conversation never happens, because people don’t talk to strangers in real life like this. They talk to strangers on the Internet like this.

Ambitious cultural projects have been made out of less than this. Think of PostSecret, which invites people to write anonymous secrets on cards and mail them to an address in Orange County, or the Race Card Project, which solicits concise thoughts about racial identity that could be expanded into stories. The RCP isn’t anonymous, but the principle’s the same — this is a search for the stories of people who don’t have a natural audience, and aren’t famous.

The common factor is sincerity, a drive to say something even though nobody is paying for it and, maybe, nobody knows who said it. It’s possible because of the bottomless well of nostalgia that Web2 made available and and (mostly) free. Before 2005, there was no place to endlessly watch every music video ever made, and no way to inform anybody watching that video of the powerful memory that “Throwing It All Away” invokes.

You should read Slutsky’s piece, which holds up and has a happy ending - YouTube won a long, stupid war against its troll commenters that was just starting in 2014. One point he doesn’t make is that a trove of stories this enormous defeats the toxic urge to collect it. I’ve spent years writing about stuff I liked, hated, or observed with no, and thinking it was important to keep it all in one place in case a future civilization needs raw material to build with.

Obviously, that’s ridiculous, and the future dystopia is going to rely on a much smarter person’s blog posts. The beauty of Sad YouTube is that it’s impossible to digest it all, so you’re never going to try. But you can appreciate the notes scribbled under the videos and get instant human connections. Even when you click on “Hollaback Girl.”

*I’m writing this after filing 3900-odd words of copy and waiting for an edit, so lay off.

Thanks for writing about Sad YouTube! Just to clarify a couple of things--I only ever wrote this one piece for BuzzFeed so strictly speaking I'm not "BuzzFeed's Mark Slutsky." I guess I was Sad YouTube's Mark Slutsky? I ran the blog (sadyoutube.com) for about three years, after which I could no longer justify staying up until three in the morning reading YouTube comments. These days I have a Substack of my own, though, that is not entirely unrelated to what I was doing with SYT. You can find it at markslutsky.substack.com if you so please!